Best Practices

Protecting Animal Species

By Katya Ortíz

Translate

عربي 普通话 Deutsch English Español فارسی Français Ελληνικά हिन्दी Indonesian Italiano 日本語 한국어 ລາວ македонски Melayu नेपाली Português Русский язык словенечки Kiswahili ภาษาไทย Türkçe اُردُو Tiếng Việt

If you require a language not listed here, or if you would like to volunteer to produce an official translation of this chapter, please email bestpractices@globalclimbing.org.

Please note that auto-translated content is not checked by GCI or the authors for accuracy.

Key lessons

Dogs at the crag: Be a responsible visitor with both wildlife and your best friend

Coexisting with wildlife means keeping interactions to a minimum

Don’t feed the animals: remember they have specific diets that we need to respect

Remember wildlife are already at home

Not all baby or injured animals need our help: aspects to take into account before helping a wild animal

About the author

Katya Ortíz is a wildlife veterinarian with a masters of science in wildlife management and sustainable development. She is a certified Leave No Trace trainer and the environmental education coordinator for Escalada Sustentable A.C., an organization based in Monterrey, Mexico, which focuses on the sustainable development of mountain sports in natural areas, taking into account the biological and social aspects of conservation to ensure access. Katya has more than ten years of experience with wildlife medicine and management, and has participated in many conservation projects with private and government environmental institutions in Mexico. She also is an activist and certified outdoor educator, having worked with children, tourist and local mountain visitors, environmental authorities, academics, and rural communities on topics surrounding wildlife care, conservation, and Leave No Trace ethics.

Peer reviewer

Carmen Black

Editor

Ludivine Brunissen

About the best practices project

The Global Climbing Initiative's best practices project taps the expertise of climbing leaders around the world to share lessons learned in crag development and maintenance, environmental conservation, equity and inclusivity, community engagement, economic impact, and climbing organizations. By making this information more accessible, we hope to foster a more united and supported global climbing community. To learn more about this project and how you can support, visit globalclimbing.org/best-practices

Introduction

Mountain sports are known for their practitioners' deep love and respect for nature and all the elements that comprise it. However, some practices that have been passed down from generations are not beneficial to the conservation of our natural areas. Nowadays, these practices have become more visible due to the surge of people interested in mountain sports and the resulting impacts on ecosystems that can be witnessed today. To ensure sustainable management of natural resources and their conservation, it is highly important to stay up to date with the information scientific studies put at our disposal regarding the best practices for the protection and care of each of the elements that make up ecosystems, not only in the climbing areas, but in general. Everything in nature exists as part of a delicate balance that we need to perpetuate.

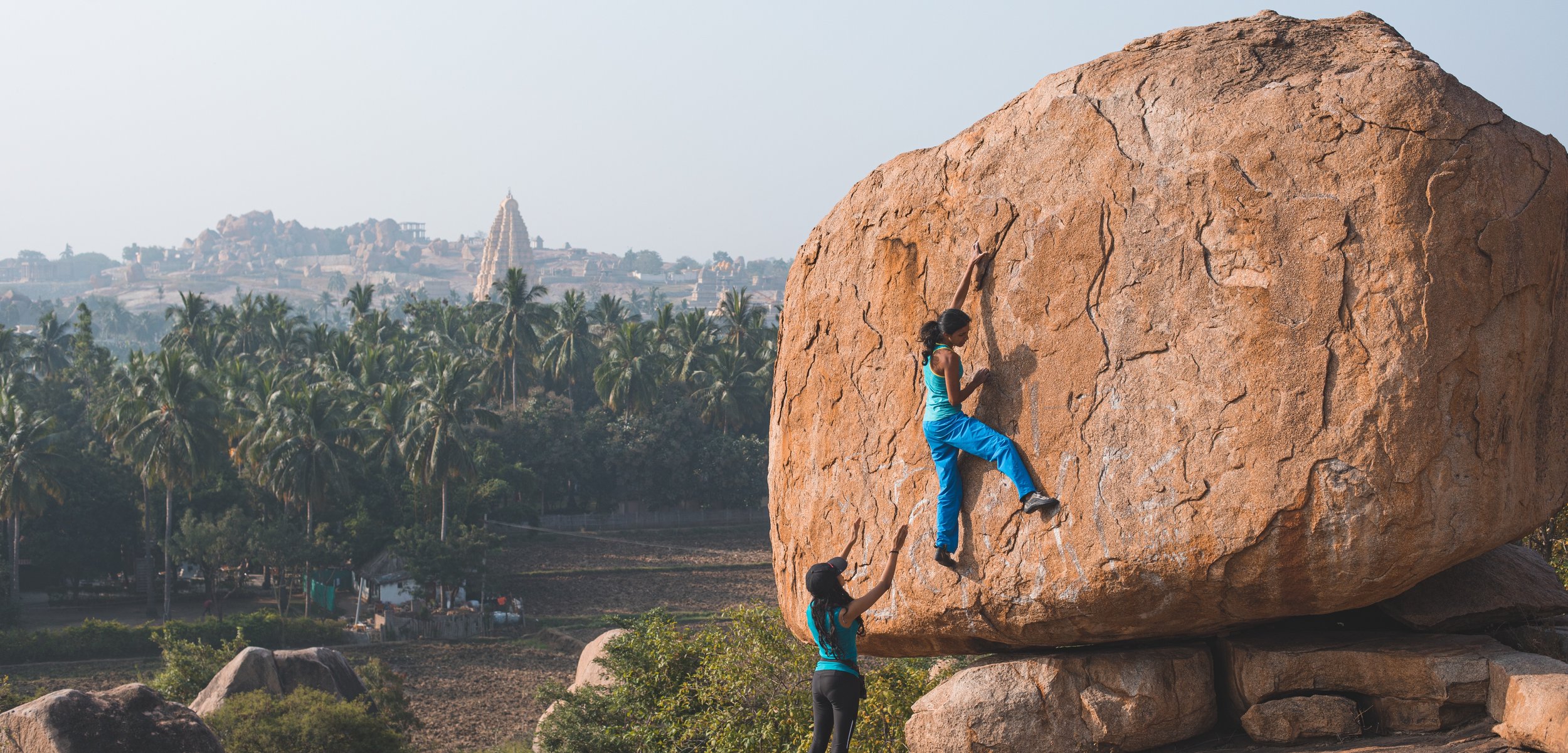

Climbing, in particular, allows us to get in close contact with wild animal species that are normally found at a distance. Not only is it important to limit the impacts we leave on climbing area ecosystems, it is highly important to realize that the potential negative effects we have on the environment begin during the approach. Recognizing these potential impacts and learning how to minimize the traces we leave behind will allow us to protect the ecosystems we love and the wildlife that lives within.

Key Lesson #1

Dogs at the crag: Be a responsible visitor with both wildlife and your best friend

There is a special feeling that comes from sharing a hike or a climbing day in natural spaces in the company of an animal that has rightly earned its title as “man’s best friend.” But, what happens when they present a risk to these places and the wildlife who live there? Sadly, science brings harsh news: dogs have contributed to at least 11 extinctions and at least 188 species are threatened because of their presence globally (Doherty et al, 2017). The sole presence of dogs at the crag can be a threat to birds, and it has been demonstrated in scientific studies that dogs, even if they are kept on leashes, affect bird populations and can displace them to the point of biodiversity reductions up to 35% and a 41% in abundance (Banks & Bryant, 2007). Furthermore, through marking and barking, dogs can alert other animals to avoid the area due to a predator’s presence, thus, potentially affecting the balance of the ecosystem (Lenth et al, 2008). This can be especially harmful if there are species at risk in the area, which can lose their nesting sites or have to compete with other species for resources. In particular, climbing sites can be the home of several species that nest in the cliffline itself (Camp & Knight, 1998).

In addition, it has also been demonstrated that a dog’s presence can increase other species' stress levels, which can make them more likely to get sick due to a poor immune response (Hughes & Macdonald, 2013). Due to being a non-native species to many parts of the world, a dog’s presence is enough to transmit diseases to wildlife, which can even lead to epidemics among them. Even if your dog has all its vaccines, it can still spread diseases when asymptomatic or through its hair, which can spread pathogens from the city to the mountain. However, what is even more dangerous is not the risk of dogs infecting wild animals, but the opposite: wildlife infecting dogs with diseases that can potentially affect us. Remember that dogs are natural predators and have an incredible sense of smell, which makes them able to quickly locate wild animals or even their excrements, which can also contain pathogens like parasites (Jenkins et al, 2011) and viruses (Kruse et al, 2004). Those pathogens can eventually be transmitted to humans via close contact or through vectors such as ticks or fleas (Mackenstedt et al, 2015). Some of these diseases can be quite dangerous and even lethal, such as ehrlichiosis, canine bartonellosis, or rabies (Breitschwerdt & Dorsey, 2000).

This is why the best way to responsibly take our dogs to the crag would be to take them to an already impacted or pet-friendly designated zone and to always keep them leashed so that their curiosity won’t get them into trouble! Remember to always prepare ahead of time and check for the regulations of the areas you are visiting: there are places that do not welcome dogs due to fragile environments or risks of interactions with the livestock of rural communities, which can threaten access due to the potential impacts of dogs on farmers’ livelihoods.

This is why the best way to responsibly take our dogs to the crag would be to take them to an already impacted or pet-friendly designated zone and to always keep them leashed so that their curiosity won’t get them into trouble! Remember to always prepare ahead of time and check for the regulations of the areas you are visiting: there are places that do not welcome dogs due to fragile environments or risks of interactions with the livestock of rural communities, which can threaten access due to the potential impacts of dogs on farmers’ livelihoods.

Key Lesson #2

Correctly coexisting with wildlife means keeping interactions to a minimum

Many people equate the terms “coexisting” and “interacting” with wildlife; however, this could not be further from the truth. Wildlife exists under a delicate balance that is important to respect. Because of this, the best way to interact with wild animals is to actually maintain distance from them. Sometimes we think that something as innocent as a close-up photo or taking a selfie with them does not hurt anybody, but these practices can actually cause a lot of harm.

Ecotourism is an incredible tool for the conservation of natural areas, but the negative impacts it can have if done irresponsibly are impossible to deny. Be it through the habituation of wildlife to human food and presence, the pressure we can exert upon the abundance and distribution of delicate species, or even through the incorrect processing of human waste and residues: all of this can lead to the emergence of diseases among the wildlife we interact with, and vice versa. It has been demonstrated that ecotourism’s negative effects can force animals to change their behavior and even disappear from certain landscapes. This can have a chain effect on the abundance and diversity of species that are key to the preservation of the places we visit (Ouboter et al, 2021). Sometimes, even visual contact is enough to change an animal’s behavior.

Because climbing is traditionally considered a low-impact activity, it might make us think that it has little to do with all this, but this is far from the truth. If not done responsibly, outdoor climbing can severely negatively impact the wildlife and ecosystems where it is practiced. Studies have demonstrated that just seeing a climber can lead to detrimental behavioral and physiological changes o a species; for example, in Glacial National Park, it was shown that grizzly bears who interacted with climbers spent 53% less time foraging and 23% more time behaving aggressively towards other bears (White et al, 1999).

Birds also often come in close contact with climbers. Studies have shown that some vulnerable species can be affected by the presence of climbers on cliffs, making them prone to fly away or avoid these areas, which affects their diversity, abundance, and reproduction success (Camp & Knight, 1998; Covy et al, 2019). Hundreds of animal, plant, and fungi species can be directly and indirectly affected by climbing (Holzschuh, 2016).

However, minimizing these impacts is possible, mostly by keeping interactions with wildlife to a minimum. This can be achieved through simple actions such as staying on trails designated for human use. Indeed, the creation of new trails or even the use of wildlife corridors can lead to a displacement of these important species, forcing them to find new safe paths, which can expose them to numerous hazards such as cars or other predators.

Chalk is also something we have to always keep in mind when climbing, as excessive chalk use can directly affect some lichen, moss, and other plant species, creating a ripple effect on important animal species such as pollinators that rely on these plants and algae for nutrition and to keep on doing their important job in the wild (Hepenstrick et al, 2020).

We can also keep direct and indirect interactions to a minimum through small actions that can make a big difference, such as managing our waste (garbage, food, and even human waste) in a responsible manner; for example, always storing our food in secure spaces, such as bear-proof containers; never leaving attractants at campsites; using smell proof bags; and also never leaving our food scraps in the crag! Remember that organic waste is still waste and can act as an attractant to wildlife, causing it to modify their habits, predisposing them to diseases, and leading to the spread of exotic plants to non-native regions.

Lastly, respecting nesting season and temporary zone restrictions is very important to give vulnerable species the chance to have a successful reproduction cycle, and to protect the dens where wildlife might find refuge in, for example, bats at the crag!

Key Lesson #3

Don't feed the animals: They have specific diets that we need to respect

Habituation is the term used when wild animals stop showing a flight or flight response or become used to close contact with humans. Several studies have shown that habituation of wildlife to humans have irreversible negative consequences (Bejder et al, 2009). These consequences can include dependence on human food, which has severe consequences for the animal and ecosystem, such as a complete change in behavior, as well as increasing wildlife’s probability of getting infected with pathogens (bacterial, viral, parasitic) that appear due to a weakened immune system from poor nutrition. Furthermore, exposure to human food can lead to dermatologic and metabolic diseases like mange, or even obesity with its comorbidities.

At its worst, the consequences of feeding wild animals can lead to death from ingestion of non-digestible materials such as plastic or aluminum and can also have disastrous consequences for humans. Indeed, through habituation and conditioning, animals start to actively look for sources of human food, thus developing atypical behaviors like destroying backpacks or learning to break into tents and houses. Severe habituation can lead them to steal food directly from humans’ hands, which carries a risk of bites, creating opportunities for humans to contract diseases. The worst kind of damage that we can exert upon wildlife through conditioning to food is to generate a dependence so intense that they stop actively searching for their natural food and teach new generations to look for human food, making these animals dependent since they are younglings.

Finally, habituation makes them tolerant of human presence, which does not mean that they start seeing us as friends, but rather that they stop seeing us as a threat. And in some cases, if the animal has a predatory behavior, this can also turn them to seeing us as a potential snack. This particular issue has been a big problem for potentially dangerous animals such as black and brown bears, where by animals that get too close to humans have to be euthanized by authorities, or die from negative consequences of habituation (Herrero et al, 2005; Hopkins III et al, 2014; Andrew & Ries, 18 June. 2019).

Key Lesson #4

Wildlife is already at home, they are not pets!

Wildlife has lots of shapes and colors! There are species that attract people’s attention due to their beauty or charisma and that are even popular as pets on social media, such as raccoons or possums, many of which are found in areas that people visit for mountain activities These animals may actively look for people because of the association of humans with food or because they don’t see us as a threat. There are also some cases in which wildlife might take refuge in your climbing gear backpack so you might want to double check after a climbing session!

Because of this, there have been times when people’s good intentions mixed with misinformation have caused them to “adopt” these animals because they think that they will not be able to survive in the wild on their own; however, this is only generating a much bigger issue. Nowadays, the wildlife black market stands as one of the biggest threats to biodiversity in the world, and actions such as these, even done with good intentions, just perpetuate the trafficking system that exists at a global level (Warchol, 2004), especially with the influence of social media, which is plagued with accounts that show wild animals being treated as pets and humanized.

Key Lesson #5

Not all baby or injured animals need our help: Aspects to take into account before helping a wild animal

Wild animal rescue and rehabilitation TV shows have been popular for many decades now; however, these kinds of programs show just the pretty side of the work involved when actually working with wildlife conservation and rehabilitation. The harsh reality of this is that for every successful rehab case, there are dozens of others that do not make it, and this is because when an injured wild animal lets itself be seen or captured, it is already going through a severe pathologic process, or is already so injured that it is unable to fight back. We should also consider that these animals may be carrying important zoonoses, which are diseases that are transmitted from other animals to humans. Rabies is a great example of this, which is estimated to cause around 59,000 human deaths annually worldwide (Fooks et al, 2014); and the recent pandemic presents another example of a zoonose that had unimaginable consequences. Not only are viruses dangerous, but also bacteria; for example, tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium spp. can put our lives at great risk and start an epidemic. Parasites are equally dangerous! For example, Toxoplasmosis is a parasite that can infect us through direct or indirect contact with fecal particles found in animals’ hair.

Also, as difficult as it may sound, some animals are meant to fall sick. In species that have stable populations, there are seasonal endemic diseases that appear from time to time. This is a natural selection process to remove the weakest individuals and let the stronger ones reproduce for the benefit of the species, or even to maintain healthy populations so that other species of prey or predator may thrive as well (Aguirre & Starkey, 1994). Remember, nature is neither good or bad, it is just nature.

It’s important to always know who to reach out to for access to correct training, tools, and knowledge to assess and take care of these cases, and to accept that not all animals can be saved. Furthermore, it is important to recognize the role these sick or injured individuals play in the natural balance of the cycle of life, whereby their carcasses will become food for other organisms that are as important as this particular animal. In the case of younglings or baby animals, we should learn about the species we’re likely to encounter in our visits to natural areas, including their reproductive seasons and habits. Indeed, there are species that do not have typical parental care and even some that do not need parental care immediately after birth, like wild rabbits for example, who only nurse their offspring once a day and then leave them hidden in their den or nest. Because of this parenting style, many people who find baby rabbits believe that their mother abandoned them and choose to take them home, which can disrupt the natural cycle and be detrimental to the cubs due to lack of knowledge on their care. Remember, it is important to respect the natural balance! Even if this implies feeling sad when an animal cannot be helped.

In case you ever find an orphaned/injured animal, here’s what you can do to help!

If it’s a baby, give it space! You can check in a couple of hours from a safe distance to see if mama comes back for it.

If the animal is very injured or the baby has been crying for help and its parents do not appear, call a local licensed wildlife rehabilitator or a park ranger - it is important to note that not all rehabilitators can take in every species, but they will know who to call.

You can help educate people to stay away from injured wildlife! Kindly explain the risks of getting near an injured or sick wild animal and why it is important for professionals to handle the situation.

If there are any dogs nearby, try to create a predator-free space by putting them outside of the injured animal’s view/hearing. Dogs will make them feel vulnerable and nervous, and this can impact their immune system.

If the animal tries to get close to you, create space and find a safe distance - remember there are dangerous diseases such as rabies that can change their behavior and put you and others in a potentially dangerous situation.

If you find a nest or an animal resting at the crag, respect them by getting off the route and climb a different one - let the other climbers know about this so the community can respect their home!

It’s important to note that every country has different authorities and wildlife rehabilitation associations, so it’s crucial to educate yourself on who you need to contact if you ever find yourself in any situation involving wildlife. Remember that if you are visiting another city or country, part of being a responsible visitor is to plan ahead and prepare, and this includes learning about the possible wildlife you may encounter while visiting a natural area, as well as the emergency numbers you should have at hand in case there’s any situation in which you or an animal could need help!

Conclusion

While there is a very special feeling that comes from coexisting with nature and the elements that are a part of it, it is important to know how to make our experience friendly to wildlife as well. Luckily, science has taught us so much and informed us that some common practices are not that useful or appropriate. To be a responsible outdoor visitor, always be open to new information, even if it doesn’t match up with some of our personal views or beliefs. Always keep in mind that nature is not cruel or benevolent, it is just an endless cycle holding a delicate balance that needs to be respected so we can ensure that natural resources and ecosystems keep surviving the expansion of human impact.

It is always important to note that as climbers, we have a direct responsibility to pass on this information, even when we are at the gym, to let rookie and seasoned climbers alike know about how we can, as a community, strive to be better outdoor users and set an example on best practices for the conservation of the places we love so much.

Information about how we can be responsible visitors to natural areas is always evolving. Philosophies such as the Leave No Trace principles are excellent examples of actions and changes that we can add to our outdoor practices and even to our everyday lives to contribute to the preservation of nature, even in urban and impacted spaces.

It is important to always keep in mind that every environment has its unique traits and needs, and to recognize all the living forms that are part of the natural areas we visit as equally necessary – even the tiniest of creatures or something that doesn’t seem “alive” like lichen are highly necessary to the functioning of these places and they all have an impact on the ecosystem – so it is our obligation, as visitors to their homes, to respect them and honor their part in the cycle of life. Let’s keep wildlife wild!

Further Reading

Get BearSmart Society (for tips on responsibly coexisting with bears and wildlife): bearsmart.com

Finding a licensed wildlife rehabilitator (US): nwrawildlife.org/page/Find_A_Rehabilitator

Leave No Trace 7 principles: lnt.org/why/7-principles/

References

Alonso Aguirre, A., and Edward E. Starkey. "Wildlife disease in US National Parks: historical and coevolutionary perspectives." Conservation Biology 8, no. 3 (1994): 654-661.

Andrew, Scottie & Ries, Brian. 2019. “A friendly black bear was euthanized after it came to love people who fed it and took selfies.” CNN. June 18. edition.cnn.com/2019/06/18/us/black-bear-euthanized-selfies-trnd/index.html

Banks, Peter B., and Jessica V. Bryant. "Four-legged friend or foe? Dog walking displaces native birds from natural areas." Biology letters 3, no. 6 (2007): 611-613.

Bejder, Lars, A. M. Y. Samuels, Hal Whitehead, H. Finn, and S. Allen. "Impact assessment research: use and misuse of habituation, sensitisation and tolerance in describing wildlife responses to anthropogenic stimuli." Marine Ecology Progress Series 395 (2009): 177-185.

Borzée, Amaël, Jeffrey McNeely, Kit Magellan, Jennifer RB Miller, Lindsay Porter, Trishna Dutta, Krishnakumar P. Kadinjappalli et al. "COVID-19 highlights the need for more effective wildlife trade legislation." Trends in Ecology & Evolution 35, no. 12 (2020): 1052-1055.

Breitschwerdt, Edward B., and Dorsey L. Kordick. "Bartonella infection in animals: carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection." Clinical microbiology reviews 13, no. 3 (2000): 428-438.

Camp, Richard J., and Richard L. Knight. "Rock climbing and cliff bird communities at Joshua Tree National Park, California." Wildlife Society Bulletin (1998): 892-898.

Covy, Nora, Lauryn Benedict, and William H. Keeley. "Rock climbing activity and physical habitat attributes impact avian community diversity in cliff environments." PLoS One 14, no. 1 (2019): e0209557.

Doherty, Tim S., Chris R. Dickman, Alistair S. Glen, Thomas M. Newsome, Dale G. Nimmo, Euan G. Ritchie, Abi T. Vanak, and Aaron J. Wirsing. "The global impacts of domestic dogs on threatened vertebrates." Biological conservation 210 (2017): 56-59.

Fooks, Anthony R., Ashley C. Banyard, Daniel L. Horton, Nicholas Johnson, Lorraine M. McElhinney, and Alan C. Jackson. "Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination." The Lancet 384, no. 9951 (2014): 1389-1399.

Hepenstrick, Daniel, Ariel Bergamini, and Rolf Holderegger. "The distribution of climbing chalk on climbed boulders and its impact on rock‐dwelling fern and moss species." Ecology and evolution 10, no. 20 (2020): 11362-11371.

Herrero, Stephen, Tom Smith, Terry D. DeBruyn, Kerry Gunther, and Colleen A. Matt. "From the field: brown bear habituation to people—safety, risks, and benefits." (2005): 362-373.

Hopkins III, John B., Paul L. Koch, Jake M. Ferguson, and Steven T. Kalinowski. "The changing anthropogenic diets of American black bears over the past century in Yosemite National Park." Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12, no. 2 (2014): 107-114.

Hughes, Joelene, and David W. Macdonald. "A review of the interactions between free-roaming domestic dogs and wildlife." Biological Conservation 157 (2013): 341-351.

Jenkins, Emily J., Janna M. Schurer, and Karen M. Gesy. "Old problems on a new playing field: Helminth zoonoses transmitted among dogs, wildlife, and people in a changing northern climate." Veterinary parasitology 182, no. 1 (2011): 54-69.

Kruse, Hilde, Anne-Mette Kirkemo, and Kjell Handeland. "Wildlife as source of zoonotic infections." (2004).

Lenth, Benjamin E., Richard L. Knight, and Mark E. Brennan. "The effects of dogs on wildlife communities." Natural Areas Journal 28, no. 3 (2008): 218-227.

Get Bear Smart Society. Responding to Human-Bear Conflict: A Guide to Non-lethal Management Techniques. Whistler: Get Bear Smart Society, 2010.

Mackenstedt, Ute, David Jenkins, and Thomas Romig. "The role of wildlife in the transmission of parasitic zoonoses in peri-urban and urban areas." International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 4, no. 1 (2015): 71-79.

Ouboter, Dimitri A., Vanessa S. Kadosoe, and Paul E. Ouboter. "Impact of ecotourism on abundance, diversity and activity patterns of medium-large terrestrial mammals at Brownsberg Nature Park, Suriname." Plos one 16, no. 6 (2021): e0250390.

Warchol, Greg L. "The transnational illegal wildlife trade." Criminal justice studies 17, no. 1 (2004): 57-73.

White Jr, Don, Katherine C. Kendall, and Harold D. Picton. "Potential energetic effects of mountain climbers on foraging grizzly bears." Wildlife Society Bulletin (1999): 146-151.

About The Global Climbing Initiative

The Global Climbing Initiative is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit equipping climbing communities worldwide with the knowledge and resources to thrive. We are the bridge connecting emerging climbing communities to the funds, gear, and skills they need to grow safely, inclusively, and sustainably. By investing in local community leaders, we are uniting the global community to build a more sustainable and equitable world through climbing.

To support the best practices project, please consider purchasing a shirt or making a donation