Best Practices

Route Naming

By Ulf Fuchslueger

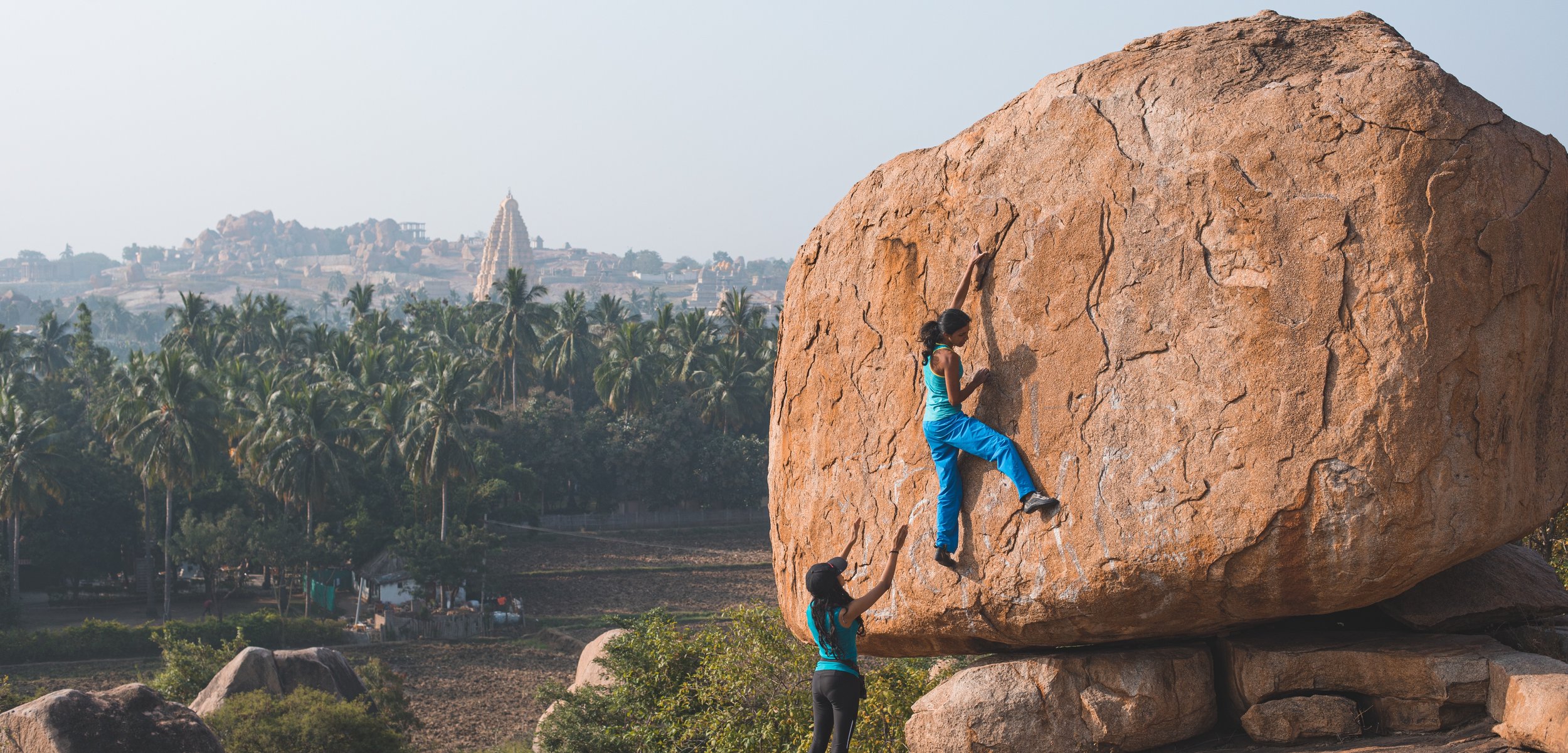

Cover photo by Casey Nguyen

Translate

عربي 普通话 Deutsch English فارسی Français Ελληνικά हिन्दी Indonesian Italiano 日本語 한국어 ລາວ македонски Melayu नेपाली Português Русский язык словенечки Español Kiswahili ภาษาไทย Türkçe اُردُو Tiếng Việt

If you require a language not listed here, or if you would like to volunteer to produce an official translation of this chapter, please email bestpractices@globalclimbing.org.

Please note that auto-translated content is not checked by GCI or the authors for accuracy.

Key lessons

Understand the surrounding conditions for naming routes

Consider themes, existing names, and creative aspects when choosing route names

Think about multilingual, multicultural and First Nations aspects when naming routes

Develop routines for publishing new route names

Establish processes for changing existing inappropriate route names

About the authors

Ulf Fuchslueger is the business development manager of theCrag, the world’s largest rock climbing and bouldering platform. Ulf has a Ph.D. in chemistry and ran a software and consulting company before joining theCrag, where he combines his background in data management in the pharmaceutical industry and his passion for climbing. At theCrag, Ulf is also responsible for the enforcement of the platform’s naming policy and as such was involved in countless route and crag naming discussions all over the world, some of which even made headlines in popular media.

Peer reviewers

Riley Edwards, Kelly Naylor

About the best practices project

The Global Climbing Initiative's best practices project taps the expertise of climbing leaders around the world to share lessons learned in crag development and maintenance, environmental conservation, equity and inclusivity, community engagement, economic impact, and climbing organizations. By making this information more accessible, we hope to foster a more united and supported global climbing community. To learn more about this project and how you can support, visit globalclimbing.org/best-practices

Introduction

Historically, in most climbing and mountaineering cultures, naming new routes, cliffs, and sectors have been the unwritten prerogative of the respective developers or first ascensionists. In the early days of climbing, routes and even summits were often named in the honor of individuals (think of the Heckmair-Route through the north face of the Eiger or the Dülfer-Dihedral to the summit of the Cime Grande), or received descriptive names such as North-East Ridge or Central Dihedral. Later, with the advent of sport climbing in the late 1970s/early 1980s and the resulting explosion in the number of routes, those engaged in route naming became increasingly creative.

This was also a time of cultural change for climbing, away from classical alpinism and towards a more playful approach to the sport, often paired with a clear break from the establishment that is also reflected in the route names of the time. While climbing became more popular in the years to follow, it still remained a niche sport followed by enthusiasts using their niche code, often strongly influenced by political and cultural events of the time.

With the explosion of indoor gyms in the early 2000s and the sport’s inclusion in the Olympics, climbing became mainstream. We, as a society, have also become more aware of our collective responsibility to not isolate or cause harm through language. As a result, often under-considered priorities such as names being G-rated and culturally respectful became of increasingly large focus for climbers. What can happen when these aspects are not considered can be seen in the example of some names that were picked up by public media, reflecting badly on the climbing community and the sport. This guideline is not intended to hinder the vibrant tradition of route naming; rather, it should help route developers and first ascensionists make considerations that will support the future growth of this sport.

Key Lesson #1

Understand the surrounding conditions

Congratulations if you are in a position to name a new route. You are probably proud and enthusiastic about your achievement, and you have every right to be so. The last task before letting the world know about your route is choosing a name. While you may name a route however you like, there are some surrounding conditions that you should consider for the benefit of the climbing community and the sport in general. So before letting your endorphins (or adrenalin) take over the job, sit back and consider the following points, which might help you avoid regretting your choice of name at a later stage:

Consider that route names are for the general public; the times when route names remained a thing of a close-knit local community, buried in low-volume self-published guidebooks, are over. Your name may end up in a newspaper next to a photo of your new creation. Choosing an inappropriate route name might have long-lasting negative consequences: publishers may refuse to use your route name in guidebooks and online applications, and climbers might refrain from actually climbing or at least recording their ascent in public logbook platforms.

Avoid offensive names. While this sounds easy and self-evident, it might not be that obvious. Avoid words or phrases that have the potential to cause harm, disrespect, or insult to a person, group, or community. The climbing community is diverse; abusive, homophobic, transphobic, sexist, misogynistic, racist, or ableist names of any kind have no place in today’s climbing world. Certain word games, inside jokes, and references to specific persons might sound funny at the moment, but actually might harm individuals or groups.

Imagine explaining your choice of route name to a six year old climber. Climbers become younger and younger, and what you might have considered a life-long project for yourself might be sent in a matter of hours by a kid—maybe even your kid—in a few years. Therefore, outright profane and vulgar names are probably not the best choice for your new route.

-

When developing routes, take the time to understand the history of the area and the people who have lived there for generations. In many places, land holds special significance for Indigenous/First Nations members of the community. Be respectful about where and when you develop, and ensure you have the permission of the local community. Engage in route naming with a level of respect that honors those who have stewarded the land before you, and seek their input. It might actually lead to more appropriate names and increase acceptance of climbing within local communities.

Key Lesson #2

Consider themes, existing names, and creative aspects

Unless you develop a brand new crag, your new route is most likely located in an existing crag with plenty of neighboring routes.

If possible, reach out to the initial developer(s)—something you hopefully did anyways before starting your development work—and find out if there are specific themes for route names in the area. For example, a crag might be called “China Wall” with names of Chinese context or Götterwandl (Wall of the Gods) with names of ancient gods; while there is no obligation to stick to a given theme, you should consider doing so, especially if it is obvious from already existing names.

Naming your route not only has the purpose of immortalising your efforts, but also helping to uniquely identify a route in a crag or area. Do your research before naming the route and check if your route name is unique for the area. This is an easy task for a small crag, but if you add your route to a mega crag like the Red River Gorge, the Frankenjura, or Fontainebleau, this task can be a bit more daunting.

The science of route naming (a sub branch of onomastics, and yes, there are even Ph.D. theses on the names of climbing routes!) has identified countless motivations for the choice of names given to routes and their change over time. The following collection, based on work by Catharina Scharf (see “Further Reading”), of directly and indirectly motivated groups of names are meant to spark your creativity; it is not complete and in no way meant to limit your choice of names:

Personal experience (Scared to Death, Silence)

Climbing requirements (Move the Roof, More Mantle than Gentle)

Difficulty and quality (Extreme Ways, Treasure of Pleasure)

Related to a person (Duncan’s Kitchen, Veronica’s Way)

Flora and fauna (Hanging Garden, Wasp Line)

Environment (Bella Vista, The Sanctuary)

Period and events (Twilight Zone, Last Minute)

Music, film, and literature (Rolling Stone, Mr. Vertigo)

Politics, history, and current events (Chernobyl, Dark Covid)

Mythology and science fiction (Zeus, Yoda)

Word games (Dizzkneeland, Bella Umbrella)

Culturally relevant (Xibalbá Uprising, Chamula Yodler)

Key Lesson #3

Think about multilingual, multicultural and First Nations aspects

You have a few weeks of spare time on your hands, and head off to a far-away location to develop some routes. Rock is plenty, regulations are few, and soon you have done a couple of first ascents. Before heading home, you proudly declare your chosen route names, but on your way home, second thoughts start haunting you…

When you develop new areas far from home, maybe even in different cultures (with different languages), it is advisable to seek local guidance before naming and publishing routes and areas. Consider local sensitivities, customs, and beliefs to avoid negative surprises or outright hostility and to promote a positive image of climbing. A name that might be considered inoffensive at home might very well be offensive elsewhere.

Consider also your choice of language. As a foreigner, it might be ok to use your mother tongue to name a route. However, taking the opportunity to name it in the local language (or use two languages together through word play) offers not only an opportunity to get more creative, but also to make your route more inviting to local climbers, furthering positive perceptions of our sport.

-

Show respect to Indigenous/First Nations cultures when naming. For example, if a crag is part of an area that is traditionally a sacred place for individuals of a certain gender, it would be a good idea to keep this in mind and choose names that do not conflict with this theme. Or if an area has recorded archeology of hunting grounds, using names that refer to hunting or meat eating negatively might not be culturally sensitive.

Learning about these cultures is a great way to not just be respectful in your naming, but also create a unique and meaningful theme for the crag. Research First Nations language relevant to the area: there might be a First Nations word that can be included in the name (see “Culturally relevant” above for examples).

Key Lesson #4

Develop routines for publishing new route names

You have done the hard work by cleaning, bolting, and first ascending the route, and you even came up with a cool name (and, depending on the local customs, you may have painted it on the wall). But how will you let the world know?

Obviously this depends on the setting you are in. If you are at your home crag, you probably know what to do. There is this climber who publishes the local guidebook, and you know to drop off the info about your new creation in the local climbing store so it eventually gets added to the next edition. But what if you don’t know that, or if there is simply no such person or store, or this author never found the time to publish a new edition?

More often than you think, routes and even whole cliffs are left unclimbed, and consequently forgotten and lost for the climbing community because they were never published. Luckily, the internet and a few community-based climbing websites make this process nowadays much easier and faster for everyone and there is no reason for any route or boulder to be forgotten anymore, however remote and isolated it might be.

As a developer and first ascensionist, it should be your routine and last step of the overall process to publish your creation with all relevant information on a community website such as theCrag, Mountain Project, or UKClimbing for the benefit of your fellow climbers and to ensure that your contribution is not forgotten.

Key Lesson #5

Establish processes for changing existing inappropriate route names

Once in a while, you might encounter a route name that doesn’t stand the test of time. It might be disrespectful, not child-appropriate, or just a bad choice made at different times and with a different audience in mind.

Changing names is a difficult and sensitive topic and should not be taken lightly. Therefore, it is very important that processes for such changes are established in a region or for a crag and that involved and concerned parties are included.

Consider the following steps:

Contact the developer or first ascensionist and explain your concern. More often than you think, they may agree with your assessment and propose a new name.

If these individuals cannot be contacted, raise the topic with the local advocacy group. They might know how to reach them or have enough authority to propose a way forward. This might also be your first step if you have good reasons to stay anonymous.

If there is no local advocacy group, you also might consider starting a discussion on a community climbing website such as Mountain Project or theCrag about the route name and try to seek consensus on the issue and a potential new name.

Once there is agreement, ensure that the new route name is published on the respective community climbing websites. Some of them allow keeping the original name as historical reference but not for general consumption. Also try to contact local guidebook authors to ensure they are informed of the change. Be aware that the old name might live on for many years in printed guidebooks.

Establishing and following such a process will ensure that climbing becomes more inclusive while respecting the sport's legacy, developers, and first ascensionists.

Conclusion

When naming a new route, developers and first ascentionists have the opportunity to impact the climbing community in a positive way. In doing so, we are taking on something very important. Research the culture and history of an area, and especially respect the views and traditions of First Nations and local Indigenous cultures. If you are not local to the area, consult with locals to develop names with local community buy-in. Last but not least, if you are a leader in your climbing community, advocate for the creation of processes for publishing route and area names and for fixing historical mistakes for the benefit of the climbing community and its acceptance in society.

Further Reading

Naming Policy, theCrag, https://www.thecrag.com/en/article/namingpolicy

Alex Casar, “Misogyny on the Rocks,” Rock and Ice, 25 February, 2020, https://www.rockandice.com/opinion/misogyny-on-the-rocks-the-tinder-p-dilemma/

Amanda Loudin, “Climbing routes are riddled with racist and misogynistic names. Meet the people trying to change it all.” The Lily, 30 November, 2020, https://www.thelily.com/climbing-routes-are-riddled-with-racist-and-misogynistic-names-meet-the-people-trying-to-change-it-all/

Catharina Scharf, “Linguistische Analyse der Namen von Sportkletterrouten in Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Onomastik,” Band 13, 2015, Praesens Verlag, ISBN13: 978-3-7069-0815-3

David Mark, “Rock climbing's new-found popularity uncovers dark past of unsavoury route names, sparking its #MeToo moment,” ABC News, 12 August, 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-12/push-for-sexist-racist-homophobic-rock-climbing-routes-renamed/12546620

Klarer Mario, “Die textsemiotische Dimension des Titels am Beispiel der englischen und deutschen Kletterroutenbenenung,” in Grazer Linguistische Studien, Jahrgang (1989), pages 39-58 (https://unipub.uni-graz.at/gls/periodical/titleinfo/4351499 )

Lanie Tindale, “Climbers caught between a rock and a social movement,” Central News, 15 August, 2020, https://centralnews.com.au/2020/08/15/climbers-caught-between-a-rock-and-a-social-movement/

Lars Hægeland, “Klatreklubb kaller ruter for «svidd neger» og «screaming jews» i ny bok,” VG, 01 July, 2021, https://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/1Bgedl/klatreklubb-kaller-ruter-for-svidd-neger-og-screaming-jews-i-ny-bok

Rolf Max Kully: “Hadeswand und Glitzertor. Zur Benennung von Kletterrouten und Höhlengängen. In memoriam Hanspeter Koeninger (1933–1990),” in: Beiträge zur Namenforschung, N. F. 26 (1991), S. 336–357

Taimur Ahmad, “Why Route Names Matter,” Access Fund, 10 September 2020, https://www.accessfund.org/open-gate-blog/why-route-names-matter

“Diskussion um diskriminierende Namen von Kletterrouten,” Web.de, 14 August, 2020, (https://web.de/magazine/panorama/diskussion-diskriminierende-namen-kletterrouten-34980218)

Michelle Leblanc, “Offensive route names and how language in climbing culture can be hurtful,” Gripped, March 15, 2021, https://gripped.com/profiles/offensive-route-names-and-how-language-in-climbing-culture-can-be-hurtful/

About The Global Climbing Initiative

The Global Climbing Initiative is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit equipping climbing communities worldwide with the knowledge and resources to thrive. We are the bridge connecting emerging climbing communities to the funds, gear, and skills they need to grow safely, inclusively, and sustainably. By investing in local community leaders, we are uniting the global community to build a more sustainable and equitable world through climbing.

To support the best practices project, please consider purchasing a shirt or making a donation